by Susan Topf

Tuesday April 16, 2024

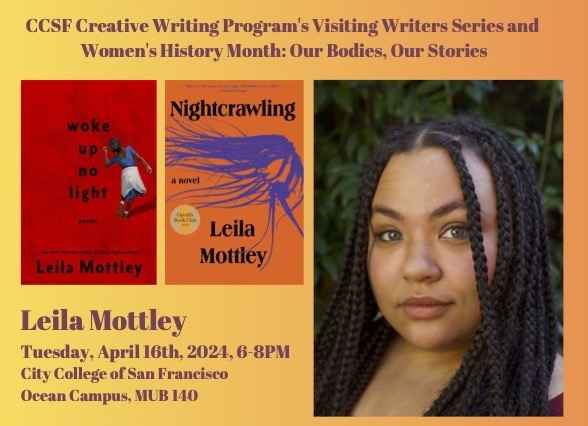

It’s a Tuesday afternoon in Poetry Month and Leila Mottley is on the CCSF Ocean Campus. In an hour, she will be giving a reading co-organized by CCSF’s Women’s & Gender Studies department, Creative Writing department, Project SURVIVE, Poetry for the People, the school of Social Sciences, Behavior Sciences, Ethnic Studies & Social Justice, and the Office of Student Equity.

Mottley is here to promote her poetry collection titled woke up no light, but she’s also at CCSF to discuss and read from Nightcrawling, her blockbuster novel ripped from the headlines. Mottley’s appearance is part of CCSF’s 2024 Women’s History Month Theme: Our Bodies, Our Stories, and she sat down with me for a candid conversation that touches on how her native Oakland shapes her work, writing as craft, and whether she thinks of herself as more of a poet or a novelist.

Susan Topf: Take me through your writing journey. When did it begin?

Leila Mottley: I’ve been writing my whole life. At six I started writing poetry. And then when I was nine, I started writing short stories. And when I was 14, I started writing novels. And this one [Nightcrawling] I started when I was 16. Most of it was written when I was 17.

ST: And now you’ve got a new book [woke up no light] released today. Congratulations. First this fiction novel and now a collection of poetry. Do you consider yourself a novelist first or poet?

LM: [Poetry] is where a lot of my roots are. But I’ve been kind of doing both of them my whole life. And I think I get different things from them both. And so, you know, it’s kind of been a part of my life. But the journey of it being public is fairly new, especially with the fiction. And it’s so funny, because I spent my teenage years, kind of like in the poetry spotlight and performing. And, you know, having that be public. And then with the novel, it was like a total switch for me. And now, kind of getting to do both, is exciting.

ST: I am curious to see how the writing process went for you, specifically for Nightcrawling: what did it stir up in you and how you dealt with any challenges. Did you have to pause during the process and step back from it? Did you use poetry such as a tool to work through what, if anything, came up for you?

LM: When I was 16 I graduated high school, and a month after I started writing it. Then I wrote the majority of the book this summer before I left her college. For me, it was in some ways a time capsule of kind of my last moments at home and a way for me to capture my girlhood, and my city, my home, and just put it in one place where it could remain knowing that it would change, and I’d never quite be able to get there again. Now from where I am, I think that’s very true. I don’t think I could or would have written this book now. So for me, it feels like this was a moment in time. Poetry, I did use throughout the writing process, but I think poetry is a harder reading experience than it was as a writing experience.

ST: There’s a lot that stirs up in the reader.

LM: Yeah, there is. I think it’s funny because when I was writing it, I was in a tumultuous place in my own life and kind of navigating this felt very normal to me. Writing through Kiara’s perspective, I was in her head so much, it didn’t feel particularly tragic or scary as the writer partially because my job was to just exist with her and, and for her, and for me, this felt a sense of normalcy in it. Whereas I think, when you’re reading the book, it feels overwhelming. There’s hurt. I think that’s kind of true of also the way that we experience adolescence. If you look at teenagers, they tell you a little bit about their experience, you’re gonna be like, “Whoa,” but when you’re an actual teenager, that’s just what it is. Normal. So I think that that’s pretty true of the writing process.

ST: It sounds like you were the character in some ways, like you were so tight and close to her. And, yeah, you developed her, but it’s almost like when we look at somebody outside, we can never fuse with them completely. It’s that distance that creates the friction or a feeling of what’s going on here?

LM: Then you have to stop and pause and process. Whereas in the writing process, I just went with it. I did it very quickly, too. I have not drafted a book as quickly as I did with this one. So I think that that also had a component of it. It’s like I got to move through it quickly.

ST: Right. And it’s interesting because you took a real life event that happened, particularly with the police, but then you also have a fictional story. So weaving between those two, how did that process go for you?

LM: I think it helps that I didn’t start with the true story or the case. It started with Kiara and the first scene I ever wrote was like the beginning chapter at the pool. That was the grounding place for it. I started with this character, and wanted to capture the sense of vulnerability and danger that she experiences. And that’s true to black girl-hood. Then I started to think “What does that mean?” on a larger plot level. The police violence and sexual violence have such an infused relationship to what it means to be vulnerable and young. So the idea of protection and who is given the right to protection ended up fitting very well with Kiara and who she was. Then I went back and started to think about the ways that I could fictionalize that case, but also like other cases, and I started doing a lot of research, and that propelled me forward in figuring out how that could be a plot, a way in which we understand the lack of protection. She’s warranted.

ST: Jumping back from process to guidance, was it your dad who got you into writing? Are there other family members or mentors who are professional writers? Or did you just know it in your spirit that you were called into writing and guidance came through your inner self?

LM: My dad is a writer, but he was a screenwriter, so I don’t think I had a full concept of that, because he went to work. Late at night he would come home, and I would hear the keyboard. That was kind of my understanding of him as a writer. I think that he definitely prepared me for the idea that writing could be something that you love. And the idea that no amount of rejection stops you from loving something. Writing is a life force and just something you need. I definitely experienced it that way. But when I started writing, I think it just came very naturally to me, I liked to read as a kid. And I think that the two kind of went together. Then novel writing was partially because I like to read.

The poetry started just from a desire to use words. I was just drawn to it. I was drawn to words and language. I used it as a way to process.Fiction happened out of a love for books, and I have developed it over time. I’ve definitely learned from watching my dad. A lot more of that is learning what it means to continue and persist until a true passion for something.

ST: It shows. I love how you go between the two different styles. How they’re distinct and discrete in their own style. Take me through the process of finding your voice.

LM: I think we each have an innate way that we write, and I think that I figured that out through poetry, the natural way in which I use words.

ST: Would you consider yourself a poet then first?

LM: No. I think because I started doing them at similar times. I was a child when I started both of them and I did them concurrently. One always took this spotlight over the other one, but I’ve been writing poetry at the same time as I’ve been writing novels and vice versa. So for me they just hold completely different realms of writing and of art, just like myself and the way that I navigate the world. So I, I don’t know, I think that I love them both.

At this point I think the love that I have for fiction has grown more and more because I’m currently writing a novel. But then if I’m writing poetry then I’ll tell you that’s my favorite at the moment. I think that was true, when I was younger, too. I figured out how I would write naturally based on the genre, the topic, or whatever I was trying to do. But I think a lot of it came from not having a construction of how I was supposed to write.

I grew up reading a lot of black women’s writing, which defies the canon. I grew up with an understanding that I could write in any way. I read a lot of poets-turned-novelists and people who did both. And that is also a specific type of writing. I think that I grasped onto the concept that I could just write freely and once I figured out what that looked like, for me, I think it’s been just a challenge to then figure out how it evolves, because you don’t need the same type of writing. When your character changes, when the topic of the poems changes, when the format changes, things have to evolve while still staying true to the way that I intrinsically know how to bend language.

ST: Was that a conscious choice to use the first person? Or did it just kind of subsume you and you went with the flow?

LM: Of the novels that I’ve written before, I wrote one in first-person, past tense, and I wrote one in third-person, past tense, and then this one was first person-present. It was my first time writing in present tense. I think I generally know when I start writing what the character is asking for. With this one, I didn’t question it. I knew that it needed to move quickly with her. That movement required that we be in the present moment with her, that we not be judging her from her own past view of herself. I knew that it was a construction study of a character. And generally, I think for me, that means first person. I’m also just not very good at third-person.

ST: We won’t tell. You’ve got accolades, everywhere!

LM: I intend to, at some point, try to get better [at] the third-person, but where I am, I think it just feels more natural. For me, I feel closer, like less distance, helps me be able to enter the character fully and then tell the story as them versus as me. I think I end up projecting more almost when I’m writing in third-person, because I feel like the narrator versus embodying the character fully.

ST: That becomes a page turner and propels you to the next journey. I am curious to hear about your poems because I have a couple here. I picked these because they’re very much tied to Oakland. Oakland not just as a location, but as the purpose, the main character. Do you do that with poetry as well, in this case Oakland?

LM: Yeah, I think especially when I was younger, in this era, yeah. I definitely was conceptualizing home a lot. I was born in 2002. I lived through the housing crisis, watched a lot of my home change. The places that I went as a child don’t exist anymore.

I think that a lot of it was also a reckoning with the fear that comes with losing something, actively losing something when you’re still young, too. A lot of my concept of Oakland was going to, in an intentional way, creating it as a person in a place and a character as it was then, because it’s changing and evolving. Like today, I still live in Oakland, I love it. It’s my place. But it’s increasingly hard to figure out what it means to reevaluate the relationship with home as it evolves over and over and over again. I look at these [poems] and I’m like, “Wow, this is an entirely different place.” So it’s so funny. I think, especially when I was a teenager, that was a lot of what I was reckoning.

ST: Yeah. It shows in [poems] as to where Oakland is not just a noun. It’s actually a purpose. And it’s a deep soul. So the soul of that journey keeps evolving and changing. Are you going to write something new or different about Oakland? What’s inspiring you right now?

LM: I definitely keep coming back to the idea of wanting to come back here but [am] not quite sure how to do it in my adult life. I’m still figuring out how to really capture it now. Some of the poems in the new collection, for me, are about Oakland, they’re not necessarily overtly about Oakland. There are some that grasp at that. But I mean, at this point, a lot of what I tried to do is keep falling in love with this city. And figuring out how to do that when, a lot of the people that I grew up with are also gone. Figuring out how that influences the way that I’m able to write the city, I was just talking to Tommy Orange. He just wrote Wandering Stars, which is his second novel, and it’s just brilliant. I think it is probably my favorite way that someone has ever written about Oakland, even more so than his first novel, which is, basically THE Oakland novel. There’s just something bright and alive about the way that he captures it and it feels very like now. I think that made me want to go back to Oakland, but [I’m] currently not doing that yet.

ST: Sounds like these poems about Oakland are a time capsule. Now you have the new collection, released today. The present moment and now let’s go to the future. Where’s the gateway opening for you?

LM: My next novel, it comes out next year. So I’m in copy edits for it. Three first-person POVs. It follows three young moms in the panhandle of Florida. And it’s been a fun book to write. It’s a book that took me six other books to get to it. And when I finally got there, it was an experiment of what if I just put everything to the side and write what sounds fun to write. I fell back in love with writing through that, especially because in the aftermath of Nightcrawling, it was kind of hard for me to conceptualize writing as separate from work and it’s been my hobby my whole life.

I’m trying to figure out how to love it again, and how to do it because I want to. It was a challenge. But I think the book that I got out of it ends up kind of reflecting that. In some ways [it] is very different from Nightcrawling just because it’s not that sad. In fact, I don’t think it’s sad at all. And I think that’s kind of part of the beauty of it, incorporating humor and fun into my work has been a big goal of mine. A way for me to enjoy the process. I’m working on my third novel now. [I’m] in the middle of that and figuring out how to find the core of it, which is process.

ST: Talking about that process, you said Nightcrawling went really quick because it was a rite of passage. It just needed to be born into existence. Now as a young adult, you’ve got this next one, which starting from such a success point of Nightcrawling makes it so challenging because you have a filter, the layer of conditioning.

LM: Yeah, there is a reader. That concept wasn’t there at all for this book. [Writing Nightcrawling], no one was gonna read it. And there’s a lot of freedom in that.

ST: How long did that take you in the process to recover the fun to write book number two?

LM: It took about a year and a half to get to the book. Then it took another year to then write the book, and then another year to revise the book.

ST: And then the current one you’re writing right now, did that give you kind of some momentum to do it? Or is there still conditioning and layers that you’re working through?

LM: I think there’s more self doubt than there ever was before, because when there’s no stakes to it, you can fail as many times as you want. Whereas I’m very aware of a timeline that I need to turn it in by, and so now I know that this has to be the one that works. And so if it doesn’t work, then I feel a lot of pressure.

ST: Does that shrink your creative process?

LM: It does. And then I can’t write inside of that. I can’t do it well, and so then trying to find space and open it up again. I think a lot of it is just a mental barrier – figuring out how I can release myself from it and from the idea of the reader and from the idea of how the books connect to each other, which is such a strange thing for me to think about. I was really young, I was 17 when I wrote Nightcrawling. The years between 17 and 22 are very long. Allowing myself growth, but also feeling the concern that people won’t get it and it’s too different. But then also not wanting to do the same thing that I did when I was 17.

ST: The writing process in itself can really stir up a lot of emotions, a lot of different ways that we need to find how to push past our coping mechanisms. For you, is one of the tools to switch mediums or switch genres? Go to poetry?

LM: I used to do that. Just let me put it aside. Sometimes I will rehearse writing novels with writing poetry as well. I’m planning on doing a very intense drafting schedule. I’m practicing the idea of creating language and interesting ways without having to feel that kind of pressure. And then sometimes I’ll say this is too much with the novel writing, and I’ll put it to the side and kind of in the lapse where I’m taking a break, I’ll write poetry. But I don’t write as much poetry as I used to. I think that’s also kind of part of not being a teenager [anymore] is not needing as much poetry. Poetry is very emotionally charged, I think. You have a lot of feelings when you’re a teenager, and I have a couple less feelings now.

ST: What would you do if you wanted to inspire someone who’s got writer’s block, or needs encouragement, to to just start or empower people to feel that liberation that you felt as a kid?

LM: I think trying to figure out how to write without thinking, without ever believing that it’s going to be written [to be read]: it’s the most beautiful thing in the world. I’m constantly trying to mimic that for myself and recreate those circumstances. Taking that pressure off yourself. The idea of submission and publishing, I think, puts a lot on what should be an expansive process. Limits in ways that I just don’t think are necessary, especially when we’re in the beginning of our careers, there’s no need to do it. And also, I think the work just suffers under the conditions of believing that you need to do it in a certain way in order for it to be palatable to somebody else.

Leave a comment