From City College of San Francisco graduate to Poet Laureate of Iowa, Forum contributor and native San Franciscan Vince Gotera talks about his poetic influences: war, the Haight Ashbury, his Filipino heritage, sea dragons, and “the city.”

Gotera’s poem below, “8-Ball in the Corner Pocket,” will be available in print in Forum‘s Spring 2025 edition, out 5/17/25!

8-Ball in the Corner Pocket

a San Francisco reverse golden shovel from “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks

We used to go, back in the ’70s, to the bona fide

real pool hall on Geary Blvd, where the genuinely

cool shooters held court with their custom cues.

We were baggers at the Commissary. Army wives

left tips for us, and the adult baggers called us

school boys, with emphasis on that second word.

We were high school kids. After school, we would

lurk where the stacks of brown bags were stored, till

late afternoon, waiting to be called over to work. Then

we would take our pocketfuls of coins and bills, and

strike while the iron is hot, hit the Town & Country

straight after work, play some stripes and solids.

We did other high school boy things too: chased

thin girls with ironed hair, sat in the park sipping

gin, drove our Chevys and Mustangs all over The City.

We listened to Cream and the Stones, none of that

jazz for us. No blues either. Went to Twin Peaks with

June and Joan, whoever wanted to kiss and make out.

We thought we would live forever, knew we’d never

die. Where are those guys now? All dispersed too

soon. How many of us have sunk the last 8-ball?

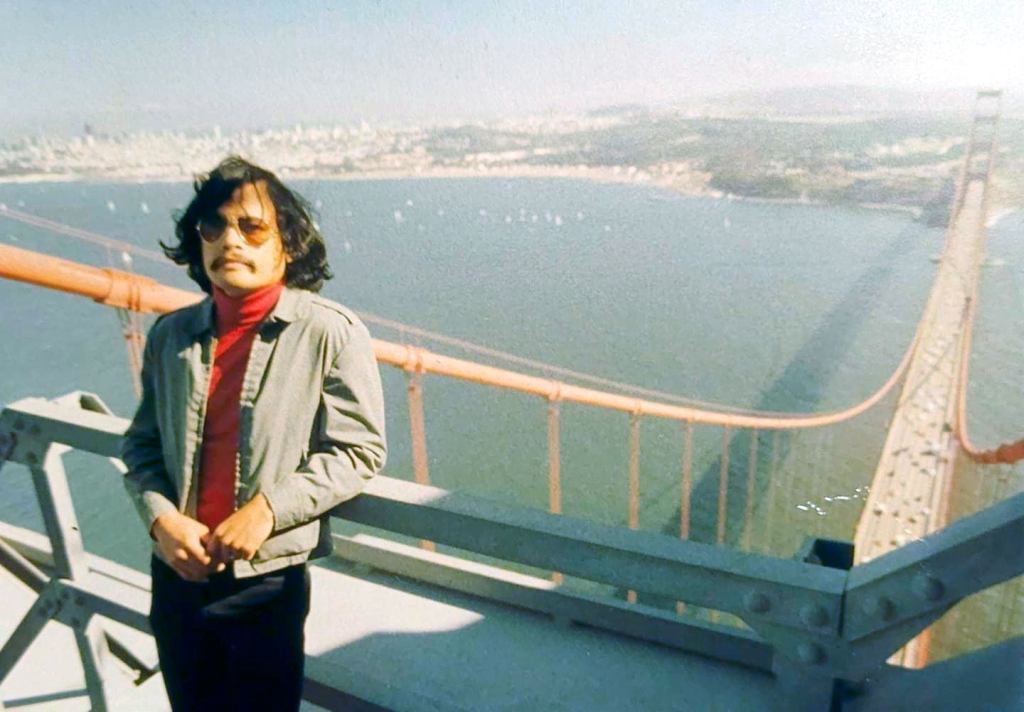

Nora Borgonovo: Today I’m interviewing Vince Gotera, a newly retired professor at the University of Northern Iowa, and the Poet Laureate of Iowa. Vince is a former editor of North American Review and Star*Line and has published six books: five poetry collections and a book of literary criticism. In addition, he is seeking publication for three new books. Currently, he’s working on a collection of music poetry.

Vince, you, like myself, are a native San Franciscan, and attended City College of San Francisco. Your 8-Ball poem references places I’m familiar with: the pool hall on Geary Boulevard, Twin Peaks …

How has being from the city influenced your poetry?

Vince Gotera: It’s a really wonderful city, and I’ve written a lot about my life there. I haven’t lived there for probably 40 years, but I come back now and then, and I’m always inspired by my life in the Haight Ashbury, where I was growing up during the hippie days, and also just the scenery and the environment of San Francisco.

I grew up in what is now called Cole Valley. I went to St. Agnes School and then to Saint Ignatius High School, and went to Stanford for a while, then went into the service and ended up going to City College after I got out.

NB: So why did you start at Stanford and then go into the service?

VG: I had a draft number of 30, so I was going, no matter what, and I was a freshman at Stanford at the time. I enlisted in order to have more control about what I was going to do in the Army. I’m what’s called a Vietnam era vet, because I never actually was sent to Vietnam, but I was in the Army during the war. After I got out, it was too expensive to go to Stanford, so that’s when I went to City College and finished an AA there, and then did a year at San Francisco State, and eventually finished at Stanford.

NB: How come? I thought that if you were in college, then you could be exempt from service.

VG: Not in my year. My freshman year was the first one where they got rid of the college exemption.

NB: How did being in the service, even though you didn’t see combat … how did that shape you, or your poetry?

VG: Well, I write quite a bit about the military. My father and my grandfather were both U.S. Army vets. They were in World War II and were in the Bataan Death March and in a concentration camp. I have written quite a lot about that. My book Fighting Kite deals with those aspects of my father’s life. Same with my collection Ghost Wars.

My dad used to tell me war stories when I was a little kid, like four or five. And I had a half brother who was a Vietnam combat vet. And, of course, my own military experience, though it was essentially peacetime service, even though the war was going on at the time.

NB: Your father and your grandfather, they’re from the Philippines. You were born here. Then you went back to live in the Philippines when you were a child.

VG: So I have some childhood memories of the Philippines, which I’ve also written about in my poems.

NB: What aspects of life in the Philippines are most salient in your writing?

VG: I was quite a small child, and so a lot of it seems kind of dreamlike to me. For example, I have a poem about catching dragonflies with my hands, which I learned as a little kid in the Philippines. That’s a poem called “Miraculous Dragonfly”, in my first book. By the way, all three of my out-of-print books are now available in my blog, The Man with the Blue Guitar.

Yeah, I write quite a lot about Philippine myth. For example, in my newest book, Dragons & Rayguns, I have a couple poems about the Bakunawa dragon, a sea dragon in mythic times. At one point, back in the ancient past, we had seven moons in the sky. And now, we only have one because of theBakunawa that used to eat the moons until people figured out that if they made noise, like banging drums, or banging pots and pans together, they could scare the Bakunawa away.

My newest novel-in-poems, Aswang Love, is the story of two aswang lovers. There are many kinds of aswang. There are vampires and shapeshifters and ghouls, and all sorts of creepy, crawly kinds of monsters.

I started doing research in grad school about aswang. I found a lot of stories, a whole lot of myth and folklore that talked about how evil these monsters were, but I wasn’t interested in that. I wanted to know about them as people. When I wrote Aswang Love, I wanted to try to get into what their inner, emotional and psychological lives were like. Two lovers – the man is a shapeshifter and the woman is a vampire – fall in love and try to live in plain sight as ordinary humans. They eventually move to San Francisco because I wanted them in familiar surroundings. It’s a long story. Anyway, this is an example of a topic that comes out of the Filipino heritage I’m dealing with.

NB: And I remember growing up in the city. People think, oh, it’s a city of love and so multicultural … so cool … but actually, growing up I saw a lot of prejudice from the city. And so, I’m wondering as a Filipino American, did you have a similar experience? And if so, have things changed in the city now?

VG: You know that growing up, like in the mid-Sixties and even through the Seventies, the world, the U.S., I should say, was very much black and white. It’s almost like there were only two races in the country, and so Filipinos (and Hispanics and Natives) were kind of in the middle somewhere, dancing back and forth, sometimes being white, sometimes being black. almost. And I write about that quite a bit. I don’t remember directly having prejudice and discrimination as a Filipino, but I know that it was around, just hearing stories from earlier generations, like from my dad. You know he actually lived in the International Hotel in Chinatown. That was where the old Filipinos lived, the Manongs.

My dad lived there actually at some point. There were a lot of old Filipinos there back in the Sixties, before that hotel was demolished. There was a famous night in 1977 when Sheriff Hongisto invaded the hotel, which was surrounded by all kinds of groups, unions and also people of color, who had surrounded the hotel, holding hands and creating a human chain around the block to try to prevent San Francisco riot police from entering the hotel. Then they did that by taking fire trucks and putting ladders up to the roof of the International Hotel. The sheriffs came from the top and evicted those Filipino residents from that hotel. What had happened there was what was politely called urban renewal.

NB: My mom told me about this. They gutted part of the Western Addition.

It wasn’t really “urban renewal.” It was really just to get African Americans out.

VG: Yes, and also other minority groups, and Filipinos were one of those groups, or at least older retired Filipinos who were living in the International Hotel. The hotel had been bought by a development group that wanted to raze it and put up condos. That actually never happened because of the public resistance. That was all tied up in the courts for years and years.

NB: But then you went off to Iowa. Now that must have been a culture shock.

VG: Actually, I went to Indiana, where I went to Indiana University, and did a PhD in American literature. While I was there, I picked up a Master of Fine Arts in poetry. And so I had certification in both creative writing and in literature.

Then I got a job at Humboldt State where I taught for six years and eventually moved to Iowa, and I’ve been here for 30 years.

NB: But why did you go to Iowa?

VG: My ex-wife, Mary Ann is from Indiana and wanted to go back home to the Midwest.

NB: Forgot about the wives. Okay, but what’s up with Iowa and Indiana? That’s very different from San Francisco. So how did that move affect your creative spirit, your poetry, or did it?

VG: It didn’t really affect it very much, because I hardly ever write about Iowa. I write about Iowa weather sometimes, but I’ve never really sort of transferred here as an artist because my work is often about other places or other things.

One exception is Grant Wood. I’ve been recently writing ekphrastic poems, that is, poems about other arts, especially the visual arts. Grant Wood is the quintessential Iowa artist. Grant Wood was a country artist. He always painted these round trees that looked like little balls on the countryside, and before I came to Iowa, I thought that was all fanciful, but it’s not fanciful at all. His paintings look very much like the landscape of Iowa.

NB: That’s a city boy outlook.

VG: Yeah. Anyway, that’s one way I’ve started writing about Iowa.

NB: And you’ve got five kids?

VG: Yes, five.

NB: How has fatherhood shaped your poetry?

VG: That’s a very interesting question. I have not written a lot about my own children. I’ve written quite a bit, though, about myself as a child with my dad.

There’s a poem, for example, that was published a couple years ago in Silver Birch Press, called “One Time My Father Said He Loved Me.”

NB: Is that poem true?

VG: Pretty much, I think. Maybe in our lives together he told me he loved me a handful of times.

He was just a very stoic man. I mean I knew he loved me, and if I ever were to say to him, “Do you love me?” he would say, “Well, you know I do.” He was that kind of guy. You know how men were in the Sixties, our parents, our fathers, I should say.

NB: My dad was Italian, so he was demonstrative.

VG: I think my dad was like that partly because he was raised by his dad, who would beat him, you know, punish him mercilessly with a leather belt. And, actually, my poem “Tatay” talks about that. I think that he wanted to be a different kind of dad to me, but he didn’t really know how to do it, so he was very careful not to be physical towards me.

NB: Were you a different kind of father to your children than your father was to you?

VG: With my own kids. Yes, I was.

My father had all kinds of plans for me. He taught me to read when I was two years old. I have a poem about that called “Dance of the Letters.” So I remember being about four years old in the Philippines, and people would come over to visit. He would hand me the newspaper, because you can’t fake the newspaper, since it’s different every day, right? So if anyone didn’t believe that I could read, he would hand me the newspaper, and of course, everybody would be like, “Oh wow!”

When I was about six, or even a little younger, he decided that he was going to train me to be a chess grandmaster. Bobby Fisher, that was his guy, and so he was going to make me into a Bobby Fisher. I was just in kindergarten and he had me reading chess manuals. That was the kind of dad that he was. He was very ambitious for me.

I wasn’t that kind of dad at all, you know. I did not want to try to govern in any way how my kids were going to turn out, or what they would do. My ex-wife Mary Ann and I pretty much let the kids choose whatever they wanted, and, as it turns out, all of them ended up being in the arts, in one way or another.

NB: You focus mainly on poetry. When did you switch more to poetry as opposed to creative writing?

VG: Well, I wrote my first poem when I was six years old. My dad and I were on a ferry. I was in 1st grade, I think, and I was looking at the sun and I wrote this poem, and then that poem eventually got published in the school newsletter. I guess I had a taste of writing and also publishing at that point. But I didn’t write any poetry after that until I was in high school at St. Ignatius. I really got into it when I became a freshman at Stanford and took my first official poetry-writing class, and then eventually went on to get a Master of Fine Arts in poetry. I have written fiction and creative nonfiction also, but in recent years have written poetry much more.

NB: What about music? Does it influence your poetic experience? I mean, do you see a correlation?

VG: I’ve played guitar for over 60 years now. I started learning to play guitar when I was 11. I’m now 72; that’s 61 years. I started playing in bands probably about 1967. A lot of that had to do with going to hippie concerts, you know. Every weekend, sometimes twice a weekend, there was a concert. I was very much affected by that, and played in several bands in high school. We played Cream, The Who, Santana. We’d play, you know, Janis Joplin, whatever. When I say Janis Joplin’s music here, that’s actually Big Brother and the Holding Company, you know, before she was solo. The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane.

Music influences me thematically. I write about being a rock and roll musician. I also write poems that have to do with musical artists. For example, in my book Dragons & Rayguns, I have a poem about Jimi Hendrix in heaven, creating a power trio in heaven with Buddy Miles and Jack Bruce.

I’m getting to the point where I’m going to put together a book of poems, a collection of music poems. These are poems about the experience of hearing music, of playing music, the lives of favorite artists. For example, I recently wrote a poem about Freddie Mercury.

NB: How do you go about teaching poetry?

VG: I’m a formalist poet. Since January 17, I’ve been taking part in the Stafford Challenge, where poets around the world are writing a poem a day for a year until January 16, 2026. Today I wrote my 103rd daily poem. Among all those, I think I have written maybe four or five free verse poems so I almost exclusively write in poetic forms of some sort. There’s a lot of haiku and tanka in there as well along with shadormas, hay(na)ku, abecedarians, and acrostics.

When I teach … for example, if I was teaching a class in beginning creative writing, their first assignment would be to just write a poem, any kind of poem, and then we would talk about them in workshop in class. But then the second poem would be a form poem, either a sonnet or a sestina, and of course I would teach them how to write those, and then we would workshop those form poems of theirs.

Our beginning creative writing courses here involve writing poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction. There is only room for a little bit of poetry there, so that little bit is half-and-half, free verse and form. But as students would advance through our different poetry writing classes, I would always encourage them to do forms. In fact, my intermediate poetry course always involved writing in poetic forms.

Introducing my students to formalist poetry is not like when I went to MFA school in the Eighties. In the poetry world in the U.S. at that time, there was what has been called the Poetry Wars, where new formalist poets, writing in rhyme and meter and inherited forms, were embattled by the ruling free verse poets. There was a lot of bad blood that happened because of that, and that was actually replicated in our MFA classes. You know, where we had the same kinds of arguments about poetry.

Thank God that after the Eighties it became okay to write in either forms or free verse, but the pendulum swings back and forth. These days, there are fewer poets doing forms. And I’m one of those. That emphasis on formalism in my own work enters into my teaching of poetry.

NB: Well, Vince, it’s been a pleasure seeing you again and getting to know you a little bit better. I hope I see you again sometime when you’re in the city.

VG: Bye, Nora. I appreciate having the chance to talk to you. And I hope to see you too, again.

NB: Bye, Vince. Thanks!

Leave a comment