Alan Chazaro in converstion with Alison Zheng and Axel Luna Condado

Alison: Who are you? Can you give us a brief background of how you became a writer? Why do you write poetry? How do those two things intertwine?

Alan: I’ve lived in every part of the Bay Area. I grew up in the South Bay, my wife is from Oakland, and I spent most of my adulthood in the East Bay. I attended community college and then went on to UC Berkeley. I’m first generation Mexican-American. I’m a citizen, and I say that because a lot of my friends weren’t growing up. Most of my closest friends were undocumented Latinx immigrants. That really shaped my view of the world and gave me insight on privilege that I think not every American has. Around the time of community college, I got my license and I got a job and [my friends] were like having to go to San Jose to get fake papers made and it was just a much more complicated process for them. That was when I stopped taking things for granted in my life, like alright, I’m kind of the guy in my group that can go to college if I want and I don’t have any excuses.

That was when I started getting serious about school. Up until that point, it was a lot of F’s and D’s and getting kicked out of programs and messing around. In eighth grade, I had all F’s. I still have my report card for motivation because it reminds me of how disengaged I was. I didn’t have anyone to tell me to work hard or to ask me how school was back then. I say all that because the one thing I always felt really good at was writing and I always liked stories. I was flunking all of these classes, but eventually I was getting C’s in English.

Once I got into community college, I started reading poetry for the first time and it just felt right. I was always into hip hop and there was enough overlap for me. I have stories to share about the people that I grew up with, about who I am, and I wanted to represent what it means to be a first generation Mexican-American from the Bay Area. Instead of doing it through rap or graffiti or other things that I had gotten into when I was younger, I was like, “It could be fun to write a book and yeah, I’m reading some old dude that died like 200 years ago and that’s kinda sick. How would it feel like if anybody picked up a book that I wrote? Maybe I can impact them positively like how these writers are impacting me right now.” My drive has always been community based: I’m from the community and I want to reach the community.

Alison: That reminds me of how you addressed boyhood in your book, “This Is Not A Frank Ocean Cover Album.”

Alan: Yeah. I wanted to capture all of that. I feel like a lot of what I was reading didn’t always reflect me. I wanted to write something so that somebody like me in that time period could be like, “Damn. I connect to this. I relate to this.”

Axel: Adding onto that, I noticed you’ve made pop culture references including Tupac, Jimmy Hendrix, Kanye, Sublime, Mustang 5.0, Levi’s, Star Wars and “fuck Donald Trump,” how does the culture and community around you influence your creative process in poetry? How have all these things, which I assume you grew up with, influenced your voice and your path as a creative writer?

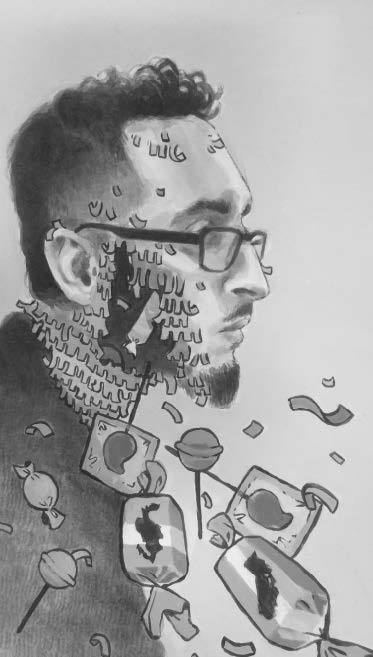

Alan: Yeah, dude. The book is called “This Is Not A Frank Ocean Cover Album” so it kind of sets the expectation that I’m responding to pop culture. Part of what I was getting at is that we live in a reality where we are all micro reflections of what is around us. None of us live in a vacuum. We are all connected to this bigger context: Music. Celebrities. Sports. Family. Social Media. We are constantly being shaped and reshaped by what’s around us, by what music I have playing in my headphones… all of that stuff: We are experiencing it and our identities are being formed by what we consume.

We are a consumer culture in the United States. Like, I’m rockin my A’s hat and I had to purchase that. I believe it’s a reflection of me and my values, you know what I mean? I always try to mimic that experience of constantly being tied to other entities. Like, the shirts that we are, the Nike’s that we’re rocking. It’s a very curated sense of self. We’re curating who we are—now, more than ever with the access to the internet and all of these things.

With the “Frank Ocean” book, I wanted to capture what it’s like to be a millenial in the Bay Area who is just constantly up on the newest shit and there’s just so much hype around everything. That’s how I live and that’s how people around me live, but not many of us are writing about it or talking about it or turning that into poetry. I wanted the book to be a fragmented mirror of our specific society with our pop culture references. Recognizing that I am who I am partially because I grew up listening to Tupac and E-40 and all these people who have shaped the way that I think about myself and about my neighborhood and about my place in the world and about the Bay Area… I wanted all of their voices and presences to be felt in the book.

Alison: I really appreciate that. When I read your writing, I felt like I knew you. It reminded me of the people that I grew up around. I feel like these voices are needed in the literary discourse. Often times, when I try to read, it’s always like some white guy talking about a barn when there are so many other voices and microcosms out there that should be reflected.

Alan: There’s definitely a vacancy. I always tell my students when they’re writing their own work… that I want to know you; I want to learn about you. For example, Axel may have an experience that I don’t and I want to know that and once you get to that point of authentic self representation, it becomes universal. You can’t fake that level of sincerity. We’re all these layered intersections of influences and the more you can tap into your specific influences… like for instance, I’m not going to try to write like Jay Z because I grew up listening to Nas and E-40… the more you trust your instincts as a writer and a creator, the more you can use your influences to tap into your voice.

Axel: It’s interesting that it’s kind of counterintuitive. The more you dig into yourself, the more people actually connect with you instead of being broad and generalized.

Alan: Yeah.

Alison: How did you come to the decision to leave your teaching career, pursue a MFA, and become a writer?

Alan: Dang. That’s a big one. Because my experience in school was more on the side of failure, I wanted to make sure that I could give back to students like me. I’m pretty sure that if a teacher had reached out to me earlier, I wouldn’t have been failing all of my classes but I never felt connected to learning in that space. Once I went through Berkeley, I wanted to go back and be that teacher that could reach kids like me and my friends. I taught for six years straight. I did Teach for America. I taught in New Orleans and Boston. It was hella hard.

I was a teacher, I was fresh out of college, and living in new places. Going from the Bay to Louisiana with no experience was a culture shock. There’s no Mexicans, no Filipinos, no Samoans… things and people that I was used to… they were not there. I spent six years working in a GED program and for a lot of those students, this was program was their last chance after being kicked out of school. A lot of those kids were living street lives and were really hustling. More than I was. I was just a lazy kid. But they were facing real problems and I had to take all of that on. I willingly did, but it was a lot to bear. After six years, I was burned out. I loved it, I had a lot of students that loved me but it’s a hard job.

During all of that time, I was writing. And, I was like, “What if I gave myself the time to regenerate? In order to help all of these students, I need to help myself too.” So, I left teaching and decided to get my MFA. I went to University of San Francisco. It was cool because they gave me a full ride scholarship and I told myself, “I am not going to pay to do something that I feel like should be free for everybody.” Also, I applied for MFA programs a few years prior and I didn’t get accepted to any schools. I could have been discouraged, but I really believed that I could do it. I spent a year prepping, reapplied, got a full ride, and offers from other schools as well. I say that to point out that people might not recognize you when you feel like you deserve it. But, if you really believe in it and you keep working for it then eventually somebody will give you the chance. I was not willing to quit.

In my last year of the MFA program, I went back to teaching full time. This time, I was at the Oakland School for the Arts and that was cool. I was teaching these hella interesting high school art kids in the day and then going to the city at night to have my MFA class and all the free time that I had was spent writing my book. That energy was important. My students were vibing with me and I was vibing with them. Then, I would go talk to adults about literature in class. Then, I would go home and reflect. It was a perfect system for me.

I’m at the point now where I’m teaching again and I’m writing. But you know, I had to teach full time to figure that out. And then, I had to write full time to figure that out. Once I gave myself the space to figure them both out, I could see how to blend them together and that is where I am at now. It took six or seven years to get to that point and I had to believe that I could do it.

Axel: Have any of your students followed up?

Alan: Hell yeah. Yesterday, somebody messaged me on Facebook and a few days before that someone emailed me. They’re constantly hitting me up. Some kids that I taught in 2009 are still hitting me up. This one student, Ricky recently hit me up and he’s like a grown man now. He calls me C-Dawg because they used to call me Mr. C. Like, what’s happening C-Dawg? Where you at? What’s good? That’s one of my favorite parts of being a teacher: all of those legacies and communities that you get to meet and connect with.

Axel: I noticed that the structure of your poems changes a lot. Like, “On Being Evicted from Earth,” it’s a paragraph. With “16 Reasons Why a DACA Dreamer Will Be the First Person to Build a Do-It-Yourself Spaceship from Simple Materials,” it’s a list. And for, “What Scientists Know About Black Holes” it’s more like a topic and note kind of style. What determines the structure of a poem and does the meaning play into that?

Alan: That’s a really good question, Axel. I think about it a lot. The answer that I’m going to give you now is something that might change over time. I’m open to change and to growth and to new styles.

Usually when I write, it’s because I feel something deep within me like a sense of rage or happiness or nostalgia. You know, something. Then, I start to ask questions. Why do I feel that? Where does that feeling come from? How can I connect it to somebody else? It becomes large very quickly. The form is a part of that process. I don’t overthink the form, I let the form think itself out. Sometimes, I’ll start out writing normally like with stanzas. But, if the topic is pushing me in a different direction, I’ll trust it and I’ll listen to that. I instinctively let the poem shape itself.

I wrote “What Scientists Know About Black Holes” when I was with my writing group in Oakland. We’re all writers of color and we try to connect once a month and write. I was thinking about police brutality and police terror. I knew I wanted to write about it because I had been feeling it in my body for awhile. This was over a year ago.

When we sat down to do our writing, the poem wasn’t coming. So, I was like, “let me start researching.” I came across the idea of black holes and I was reading all these articles during our writing session. Like, four or five articles. When I say read, I mean skimming them for cool stuff. I noticed they all had these different phrases that were connecting with me and it felt like they had some deeper meaning. I was copy/pasting quotes from these sources and bullet pointing them on my document. I didn’t know at the time what I would do with them, but then I started writing responses to all those bullet points.

The form became exactly like what you said, dude. It was a note taking style where I was allowing the content write itself. This happens with a lot of my poems. It’s rare that I would change the form. I trust myself. I used to try to force things, but that was hella work and it didn’t feel natural for me. I’ve come to the place now where I trust instinct.

I do intentionally try to experiment though because we need to push ourselves as writers. I read hella poetry and if I read something that’s interesting then I’ll play with that poetic form. You should push yourself formally. Once you practice enough, then it’ll start to happen naturally. A NBA player doesn’t need to think about how to do a three pointer, it becomes a natural flow for them. With form, I’ve been training and training so that when it’s game time, I naturally know the move that I have to use.

Alison: Can you speak about what it’s like to be a writer of color in a space that has historically been occupied by white men? Have you seen changes over the years?

Alan: This is very much on the forefront of my mind. I went into writing and teaching because I didn’t feel like I was represented in either fields. There weren’t a lot of Latinx people that I could relate with directly doing what I wanted to do. Shout out to those that did like Luis J. Rodriguez—he’s a writer that really influenced me. Shout out to the pioneers, but there needs to be more. I went into writing in ~2009 and I felt like we were super marginalized. We were this exotic other. It was like, here’s the one Latinx writer in a group of white men and white women. I have to say that’s starting to change. We’re living in an American renaissance or even a global renaissance. My theory is that when Obama went into office, it inspired people directly and indirectly. Like, yeah we can take up space and we can be represented. And with social media, people have been given more access to representation without institutional gatekeeping. Back in 2002, I couldn’t just go to a publisher and get published. There are young teens now that are getting their works published because they can just put that stuff on IG or Twitter and blow up. Then, boom. They’re out there and they’re getting represented.

If you look at the publishing stats nowadays, there’s way more people of color or people that come from marginalized communities. It’s like a double edged thing. People are realizing they can make money off of us. The market exists now, and it also means that we have more access.

Axel: Growing up, reading a lot of white writers… I always felt a disconnect with what they were writing about. Like, the things they wrote about was almost romanticized. Reading people from similar backgrounds as me is less me trying to understand and more so just me trying to relate to it. And, it helped me become more enthusiastic about learning.

Alan: Yeah. It’s a very validating experience. I’ve felt that way too.

Axel: In the poem, “What Scientists Know About Black Holes,” you talk about black holes in America. Some of the ones that stood out to me were social injustice and police brutality and the criminal justice system. The line that stood to me the most is “light explodes brightest in the dark.” I wanted to hear your take on what that light for America’s black hole is?

Alan: Whoo. That’s such a great question. Moments like this where we’re all connecting. People putting their egos aside. Deconstructing capitalism. I talk to my wife a lot about this. To me, everything we’re experiencing that’s horrible on this planet: climate change, gentrification, violent racism, the criminal justice system… all of that to me… stems from US capitalism, the idea to consume, to hoard materials, to exhibit excessive and unnecessary wealth. And where does that stem from? White male patriarchy, ego, and pride. I try to identify: when am I taking advantage of my privilege(s)? Especially as a US citizen that participates in the US machine of capitalism on a daily basis? I don’t want to blindly participate in those systems of exploitation.

The light comes from people being willing to do the work to call themselves out and keep themselves accountable even if it is indirect, and working against those things. I’m not saying I’ve done it perfectly, because I haven’t. I am committed to bettering and helping other people, especially young people, when I can and however I can. With poetry, I want to make people feel good so that they can tap into their own stories and represent their communities. Those are actions that I try to take personally.

We have so much to do as a society, and I try to help my friends and people that I feel like are perpetuating these systems. And, a lot of them do this out of sheer ignorance. They’re not hateful people. I don’t think they’re aware that their actions are contributing to the injustice of our society but they are, so I try to call people out when I can. But, that’s also exhausting. Ultimately people have to come to that realization in their own way. Things like art, culture, and traveling teaches people to be better without beating them over their head with it.

And, I feel like that light can become more clear when shit gets worse. Like with Covid-19 and the BLM movement, I feel like people are starting to see, “Damn, we do live in a hateful ass country and what’s my role in that?” When things get darker, there’s more potential for us to see the light within ourselves and we can work against the darkness.

Alison: In your poem, “What the Alien Tried Saying In a Language He Does Not Speak,” there’s this line: “maybe I need more practice/on how to untether myself/from myself. On how to spit out my own/definitions. On how to speak in a body/unbroken by borders.” It stood out to me and makes me think about how people of color and immigrants inhabit bodies that are in many ways defined by arbitrary borders. It makes me wonder, how do we define ourselves? How do you define yourself? I’m also curious if your time spent in Latin America has changed shaped your perception of your own identity.

Alan: Last year, I left teaching and was traveling with my wife. I acknowledge that it’s a privilege, as a US citizen, to be able to leave like that. My wife is also a teacher and because of that we travel a lot. We’ve thankfully been able to hit up different parts of Asia, different parts of Europe, different parts of the world. Last year, we stayed in Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Mexico for almost eight months. We wanted to do a full year but Covid-19 happened. As I’ve been able to travel more, I’ve gotten to see the nuances of what it means to be Latinx in the states vs. what it means to be Chilean vs. what it means to be Argentinian vs. what it means to be Brazilian, etc. There are so many layers to different people and cultures. A lot of US citizens are comfortable in their little capitalist bubble watching the NFL and drinking Bud Lite or whatever. I’ve lived in different parts of the US so when I bash on the US… I’m just saying, you have to know your own place to not like it.

I’m not exotifying other places. I know that they have their own issues. Living in other places though has helped shape my perception and understanding of the US better. In the US, we impose borders on ourselves. When I left for Mexico, a lot of people told me not to go. My own relatives told me not to go. But, I felt safer there than I do here. In Mexico, everybody is like let’s enjoy being alive together. In the US, some white dude will drive up to me and flip me off. I consider these to be borders. We’re so distrusting of each other. We’re obsessed with bordering ourselves off from everybody in as many ways as possible. I’ve never experienced any country that was as mentally bordered off as the US.

Recommendation: Take out that American fear and allow yourself to experience new places. But also, be street smart about it 😛

Axel: Coming from a Hispanic background myself, I know Catholicism is deeply ingrained in family structure and the culture itself. Did religion play a role in your creative path and has it influenced your poetry in any way?

My mom wasn’t around. Her and my dad divorced when I was 3. My dad is very much not the stereotype of a Mexican machista. He’s very gentle, kind. I call him my dad but he’s like my abuela. He’s tender. He took care of us. My mom was the wild one. When I was in high school, she was going to more parties than I was. We’re close now, but I grew up in a house with just my dad and my older brother which is super unique. I don’t know any other Mexican kid that didn’t have a female presence. My dad was doing laundry and cooking and working, you know? In that sense, I grew up in a weird masculine space because all of my homies was also all guys. There was never any woman until we got older, like in high school. That’s my way of saying, I didn’t have a traditional upbringing and because of that, there was no religion in my house.

My dad was kind of a weirdo. All we did was watch sports and talk about sports. The only place where I did get a sense of religion was from my abuela, who lived in Mexico until her final days. She was very religious. I never subscribed to religion. From a young age, I was questioning institutions and religion was one of the early ones. Not to knock on people that believe in it. I can’t knock where you get your faith from. But, for me, it just never spoke to me based on what I was seeing. I don’t know if it comes up much in my work. But you’re right, it has a strong grip on the Mexican community.

Alison:Sports can be a religion! Ok. My next question: As a writer of color, do you ever worry about tokenism in your writing?

Alan: When I started my MFA, I was very much like, “I’m a community poet. I’m about La Raza.” You know what I mean? And my earlier poems were playing into tropes and easy stereotypes and a few of my classmates and professors would call me out on it, which in retrospect, I’m thankful for even though in the moment, I was like “You don’t know me. You don’t know where I’m coming from!” but now that I look back as a creator (more than as a person), I read those poems and I’m like, “They’re so bad.” It was trying too hard. But, that’s fine. I think every writer needs those stages where we figure out what is authentically us versus what is portrayed as us. I needed to get those poems out of my system early. Now, I look back on them and I can identify that they were tokenizing. I was the Mexican kid in my class so I felt like I had to be writing about like… my abuela, you know what I mean?

My professor, a Japanese-Korean American woman, told me that we all have many selves that occupy us. Like, I am a Mexican-American male but I’m also an.. anime fan, an Oakland A’s fan, a second child, there’s a lot of other selves that I hold. I started becoming more interested in the weirder, stranger parts of me that are unexpected. I try to write more about that now. Some of my Filipino homies put me on anime a few years ago and it’s like my favorite thing now! So, now I try to think about how… I can for example, let anime inspire me. Like how does the narrative work? How does the character development work? How can I capture something like that in my voice as a writer?

Axel: A few of your poems include some elements of astronomy from aliens to alternate universes and even spaceships? Is astronomy one of your interests or is it more a poetical device?

Alan: It’s a bit of both. The poems that you read (related to astronomy) are all part of a book that I’m writing right now where I want to make things more weird, interesting, and creative for myself. I was watching a lot of Star Wars, grew up watching sci fi stuff, and wanted to take these elements of the real world and mix it with sci fi while embracing the fact that I am Mexican-American. I wanted to stir that into a pot and mix it. I’m working on book right now called “Pocho Boys Build Spaceships Too.” This forces me to break the tropes; to not just replicate the same thing, but to consciously and actively break stereotypes. I’m interested in borders and gentrification, but writing a rant about it vs. me writing a rant about being evicted to Earth… it just seemed like that concept gave it a different layer which made it more intriguing for me as a reader.

I’ll give myself a random assignment like watch an old sci fi film or read an article about asteroids and then work on my own prompt: What is calling to me from this? What can I write about that? That’s part of how I’m challenging myself as a writer in an organic way without tokenizing myself. Like, I’m not writing just another abuela poem—let’s put my grandma in a space suit and see what that’s like! The politics is there and it’s easier to digest when it’s not pummelled into your face. I’m still very down for BLM and I want to tie it in to my work subtly.

Axel: As a closing question, do you have a message to CCSF writers to help encourage them?

It might be cliche, but I’m a strong believer that everyone is a poet and is a creative artist but capitalism beat it out of us. Everybody has a story and everybody has the ability to create. Sometimes, it’s not the right time or we don’t see those opportunities. But, we have to believe in ourselves. Every voice matters. Just because you’re not at Stanford doesn’t mean that you don’t have a valuable book to write. Personally, I would always pick the community college book over the Stanford book. Those of us that have gone to community college have experienced some real shit.

Embrace your textures, embrace your richness, embrace your history. It is a strength and a weapon. Once you see that you can flip pain, struggle, success, joy, and marginalization into a weapon, you can become a very dangerous person. And I don’t mean it in a bad way. Like Tupac would say, like how he said that an educated Black man is the most dangerous thing to the system because it is so powerful. You can harness that and you have to trust it. It’s beautiful to see.